![Conrad Poirier [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.soundexchangetampabay.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Feature._Pressing_BAnQ_P48S1P10527.jpg)

Some people buy records simply for their entertainment value, while others buy them for reasons above and beyond entertainment. Within the record-collecting community there are many styles of collecting, each focusing on different aspects. This article will focus on collectible records known as “first pressings” and also describe how test pressings and white label promos fit into the picture.

Before I start, I will tell you that I will pose at least as many questions about “first pressings” as I answer. This is not an exact science. There is no one source for this information, but rather it is based on the collective observations of many collectors. Some facts are firmly established, while others are more nebulous. We are all constantly obtaining and learning more about this topic.

Let’s start at the very beginning and realize that when we begin to talk about first pressings, we are really talking about documenting the output of the record album manufacturing process. Typically, a first pressing is defined as what the actual record album looked like when it first came off the manufacturing line. This includes the record, jacket, inner sleeve, inserts, posters, and many other small items of interest. Any change from that original record and its packaging, and it could be referred to as a “second pressing.” That may seem like a pretty clear-cut definition, but in practice it can be more complicated. Start with the fact that the record album itself does not specify its pressing number or give any indication that something has changed. If the entire manufacturing process had been carefully controlled and documented down to every minute detail, then it could be said with much more certainty exactly what pressing a particular record is. However, that never occurred. Given the significant number of changes that have occurred for many record albums, it could quickly become a topic of hair-splitting minutiae. Some things just don’t much matter to collectors, while other things do. Indeed, some details and changes are best defined as variations, oddities, rarities, etc.

When looking at any manufacturing process, a steady stream of output can be interrupted by problems that could cause a change to the end product. While some types of manufactured goods must meet highly-defined standards, the objective with producing vinyl records was to get a product of reasonable quality out the door and into the awaiting public as quickly as possible. So when it comes to making records, let’s say that production is sailing along smoothly except that they have run out of record label blanks (stock labels before the imprinting of the album specifics). They could shut down the line and wait for more correct ones to arrive, or they could scrounge up some of the old style labels that went unused when they switched label designs and use those. (Keep those record presses rolling!) Since record labels are one of the primary means of identifying which pressing number a record is, using old label blanks can cause a “temporal disturbance” and make a certain record look as if it were produced at an earlier time. Examples of this type abound. Sometimes you find records with different labels on the front and the back of the same record, or sometimes you find that two records from a two-record set have different labels. Now consider that a record manufacturing plant could have multiple manufacturing and assembly lines. Also, many companies had multiple manufacturing plants that were regionally located. Beyond that, when a particular record became a super-hot seller, a record company could enlist the help of outside manufacturing companies to help satisfy demand. So without further belaboring the point, there can be many significant variations and some very minor variations that could occur and can cause confusion amongst collectors as to what pressing a particular record is. So even if these all could be properly sequenced and numbered, at some point it becomes fairly meaningless.

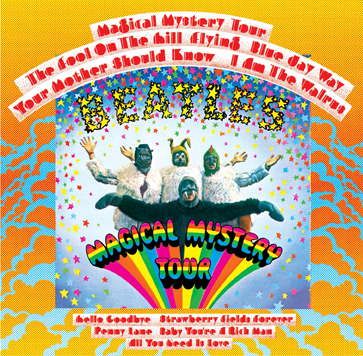

Another variable in practical terms is whether or not the artist or record company is highly collectable. Slight changes or variations for many records are relatively unimportant, but for groups like the Beatles it can cause the collector to delve deeply into minutiae. If you turn back the hands of time to the 1970s, a “first pressing” of Meet the Beatles was pretty much defined as a pressing on the Capitol “rainbow” label, a label so named because of the band of the color spectrum that encircles the perimeter of the record label. But as time has passed, and numerous subtle changes have been identified and time-sequenced with some sense of accuracy, you find references to whether each song used ASCAP or BMI copyright identifiers after the song title on the record label and jacket. You can now see descriptions such as “no BMI references” or “three BMI references.”

So what makes this information become useful or burdensome? While it is noteworthy, does it really matter much? It certainly raises the question as to why anyone really cares about “first pressings” to begin with! So let’s ask the question: Why do collectors care about first pressings?

It is my opinion that if you could absolutely identify a particular record as being the very first copy of a record album to ever be produced, then it could be extremely valuable to the collector market. Why? There are two reasons: this would be the closest that you could get to the artist and the actual performance via record, and it would potentially be the best sounding copy to ever be produced.

So with the goal of trying to find the earliest copies that were ever produced, collectors are more and more paying attention to the information that is physically etched onto the vinyl record itself in the blank area – known as the “trail-off” – between the record grooves and the record label. Manufacturing information is etched onto the mold (stamper) that actually produced the record. Each manufacturer placed whatever was meaningful to them in that area. One item of interest was to identify the stamper number that made the actual record. This was done for quality control purposes, but the avid collector can use this information to his benefit. The assumption is that the lower the stamper number, the closer to the beginning of production you get. In many cases, stamper numbers can be ascertained by studying this trail-off information. RCA records used a format where the catalog number had a suffix attached to it to identify the stamper number. An example is 2345-1S, where the catalog number is LSP-2345, and the 1S is the first stamper.

You may ask why collectors care about stamper numbers. From a sound quality perspective, the best possible sounding recording exists on the “master recording.” As copies are produced via the extensive and elaborate manufacturing process (see the video of “How Records Are Made” elsewhere on our website), there is a very slow, steady degradation of the sound quality due to the fact of handling and copying. So records made from the very first stamper should sound the best, albeit by a small incremental difference. The manufacturer made thousands of records from the first stamper and then replaced it for quality reasons with a fresh stamper called stamper number two! This process goes on ad infinitum. Now if you are really paying attention here, you will realize that the manufacturer changed the stamper because it was getting old and was not producing an end product as good as a new stamper would produce. So the first record produced from a stamper sounded better than the last record produced by that stamper. But also you can see that the first record produced from the second stamper probably sounded better than the last record produced from the first stamper, or they would not have changed stampers! But unfortunately, there is no sequential pressing number available from each stamper. So while it is reasonable to state that the lower stamper numbers sound the better than higher stamper numbers, you still have to listen to the record and compare two copies to see if there is a difference and one is better than the other. Low stamper numbers are not an assurance of the best quality, just a tendency towards the best quality. Listening still trumps all.

Again the question is why collectors care about this. From what you’ve learned, you can probably see that the earliest pressings of a record are likely those will those that sound the best. While these early copies do not sound as good as the original master recording, they are the best available quality recordings that you can buy. But what happens as time passes? The original master recording degrades from age and use, while the vinyl record – if it has been handled properly and had little to no play, generally degrades very little. Master recordings can get damaged, lost, or even destroyed, which could leave our first pressing vinyl record the best sounding copy of that performance on the planet! So now you know why collectors care about first pressings! The copy of a record that you hold in your hand could be the best quality example of a performance in existence. And if you really care about it, you will want to find it, protect it, and cherish it for what it might be.

So what is the definition of a “first pressing”? Is it what the album looked like before any changes occurred, or before a label change, or only produced from the first stamper, or yet another variation on any these? It varies in how the term is used and, frankly, cannot be taken too literally. When looking at records at our stores, or any place where more information about a record is provided, pressing number needs to be taken as a helpful indicator of its age and potential quality rather than an absolute definitive fact.

If you have really understood this article, then mentioning the terms “white label promo” or “test pressing” should really light up your eyes. Test pressings are just that: a pre-release version of an album sent to a handful of industry insiders for their review and comment. Obviously these are really the first copies to be pressed and may actually be unique if the recorded material was changed in any way before its commercial release. White label promos are generally the next copies pressed. They are almost without exception identical to the commercially released “stock copies.” Promos are sent out to radio stations, DJs, newspapers, and magazines in hopes of getting a favorable review or some airplay. They are more common for newer artists the record companies are trying to promote, which is why you don’t see that many promos for the well-established artists. While white is the most common color for the labels of promotional albums, the term “white label promo” is not to be taken literally. Special promotional labels came in many different colors, some with the standard label but stamped with “Promotional Copy,” “Preview Copy,” or “DJ Copy.” So why were these records distributed with a non-standard record label? Simply so that they could be identified by the record companies as a giveaway item so that record stores could not return them to the record companies for credit. Nor were they supposed to be sold at retail.

It is easy to understand why test pressings and promotional albums command a premium to the collector market, especially for the big named groups. But for many really obscure artists that had no commercial success there could actually be more promotional copies in circulation than stock copies! So while promotional copies make fantastic collectables, keep this in mind when it comes to their selling price.

Sign Up For Our Newsletter

Sign Up For Our Newsletter

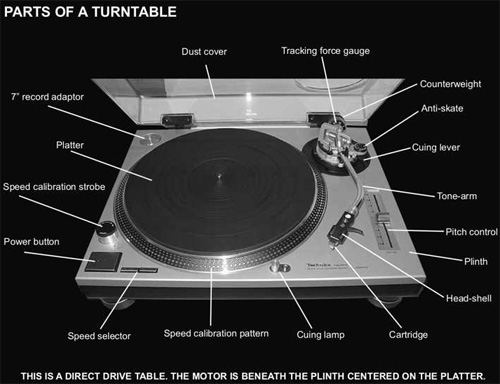

The phono cartridge contributes to unwanted noise as well. It is a sound transducer and can be thought of as a specialized type of microphone in that it picks up the vibrations from the stylus as it tracks the record groove and responds to its encoded vibrations.

The phono cartridge contributes to unwanted noise as well. It is a sound transducer and can be thought of as a specialized type of microphone in that it picks up the vibrations from the stylus as it tracks the record groove and responds to its encoded vibrations.

![Conrad Poirier [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.soundexchangetampabay.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Feature._Pressing_BAnQ_P48S1P10527.jpg)